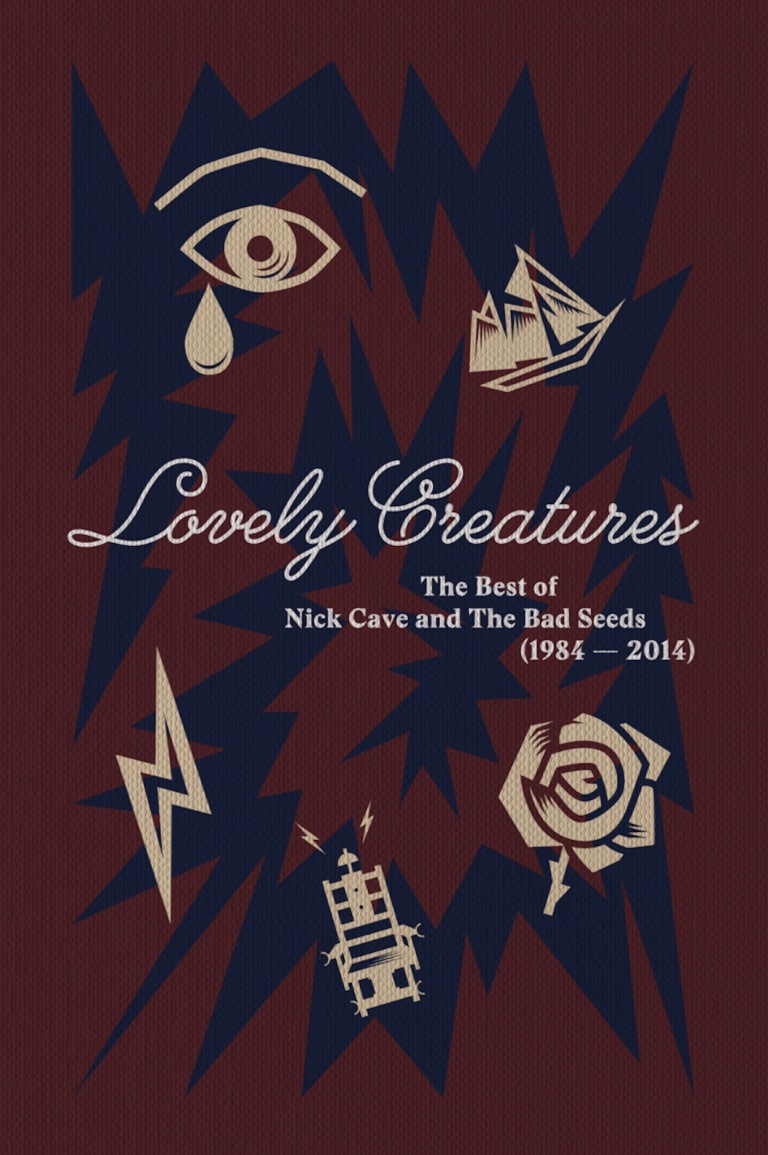

Of course I own Lovely Creatures Limited Edition Super Deluxe with Hardcover Book (yes, that’s the actual name of the thing) and obviously it’s lovely and super and deluxe and the hardcover has a mermaid, a wild rose, the electric chair and the body of Sorrow and so on.

Inside the book, among the hundred fabulous photos you can very well imagine, I found a particularly interesting essay about Nick Cave’s Australian sense of humour. It’s called “Like and Atom Bomb: Nick Cave and the Australian Language of Laughter” and it’s the edited version of the same article from Cultural Seeds: Essays on the Work of Nick Cave, by Karen Welberry and Tanya Dalziell (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009)

It does a good job in explaining why Nick Cave is not a Gothic price nor a Byronic hero, after all, but basically a postcolonial guy who’s become a minor deity through a satirical interpretation of the sublime.

This is how the original version begins.

Is this man joking?

Nick Cave recently told a London journalist that he planned to have a life- sized statue of himself ‘sat atop a rearing horse’ erected smack in the middle of Warracknabeal, the Australian country town in which he was born. He continued:

We found out it was going to cost an extraordinary amount of money so it was decided to make a film of the whole journey of this thing. We were going to make it in England, ship it to Australia, put it on the back of a truck, and dump it in my home town. […] If they didn’t accept it we were just going to drive it out to the desert and dump it…

As the journalist herself remarked, this story was probably Cave’s idea of a joke. Only she wasn’t entirely sure. When asked, members of Cave’s band did back up his ‘spectacularly unlikely claim’. And, the more one thinks about it, the idea is actually strikingly resonant. Many North Victorian country towns, and especially Wangaratta, where Cave grew up in the 1960s , were once bushranger territory: the signpost on the Hume Highway reads ‘Legends, Wine, and High Country’. Most of these ‘legends’ do involve white men on rearing horses – ‘the Man from Snowy River’ perhaps being the being the prime case in point. There is, additionally, significant historical piquancy in those remarks about ‘making’ something in England, ‘shipping’ it to Australia, loading it ‘on the back of a truck’, then ‘dumping’ it in the desert. This was the colonial pattern, and it continues to be a metropolitan assumption about what ‘the bush’ is good for. ‘The Man from Yarriambiack Creek’ (my suggested title) probably would make a poignant film. Cave, however, went on to quip ‘I’m Australian – even we don’t know when we’re joking and when we’re not’ and the journalist, perplexed, left it at that.